How Much Is A Denarius In Today's Money

Denarius of Octavian and Marking Antony, struck at Ephesus in 41 BC. The coin commemorated the two men's defeat of Brutus and Cassius a yr earlier too as celebrating the new 2d Triumvirate

The denarius (Latin: [deːˈnaːriʊs], pl. dēnāriī [deːˈnaːriiː]) was the standard Roman silvery coin from its introduction in the Second Punic War c. 211 BC [1] to the reign of Gordian 3 (AD 238–244), when information technology was gradually replaced by the antoninianus. It continued to be minted in very small quantities, likely for ceremonial purposes, until and through the Tetrarchy (293–313).[two] : 87

The give-and-take dēnārius is derived from the Latin dēnī "containing ten", as its value was originally of 10 assēs.[note i] The give-and-take for "money" descends from it in Italian (denaro), Slovene (denar), Portuguese (dinheiro), and Spanish (dinero). Its name too survives in the dinar currency.

Its symbol is represented in Unicode every bit 𐆖 (U+10196), all the same it can besides be represented every bit X̶ (upper-case letter X with combining long stroke overlay).

History [edit]

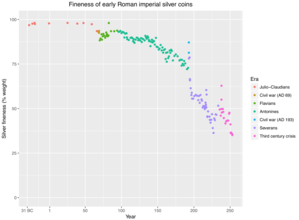

Starting with Nero in AD 64, the Romans continuously debased their silver coins until, by the terminate of the 3rd century AD, inappreciably any silver was left.

A predecessor of the denarius was first struck in 269 or 268 BC, five years before the Commencement Punic War,[3] with an boilerplate weight of 6.81 grams, or ane⁄48 of a Roman pound. Contact with the Greeks had prompted a demand for silver coinage in addition to the statuary currency that the Romans were using at that fourth dimension. This predecessor of the denarius was a Greek-styled silver coin of didrachm weight, which was struck in Neapolis and other Greek cities in southern Italian republic.[iv] These coins were inscribed with a legend that indicated that they were struck for Rome, only in manner they closely resembled their Greek counterparts. They were rarely seen at Rome, to estimate from finds and hoards, and were probably used either to buy supplies or pay soldiers.

The outset distinctively Roman silverish coin appeared around 226 BC.[five] Classical historians have sometimes called these coins "heavy denarii", but they are classified past modern numismatists as quadrigati, a term which survives in one or two aboriginal texts and is derived from the quadriga, or four-horse chariot, on the contrary,. This, with a two-horse chariot or biga which was used as a contrary type for some early denarii, was the prototype for the most common designs used on Roman silver coins for a number of years.[half dozen] [7] [8]

Rome overhauled its coinage shortly earlier 211 BC, and introduced the denarius aslope a brusk-lived denomination chosen the victoriatus. The denarius contained an boilerplate 4.v grams, or ane⁄72 of a Roman pound, of silvery, and was at first tariffed at ten asses, hence its proper name, which means 'tenner'. Information technology formed the courage of Roman currency throughout the Roman Commonwealth and the early Empire.[9]

The denarius began to undergo irksome debasement toward the end of the republican catamenia. Nether the rule of Augustus (27 BC – Advertizing 14) its weight roughshod to three.9 grams (a theoretical weight of ane⁄84 of a Roman pound). It remained at well-nigh this weight until the time of Nero (AD 37–68), when it was reduced to i⁄96 of a pound, or 3.4 grams. Debasement of the coin's silver content continued after Nero. Later Roman emperors too reduced its weight to 3 grams around the late 3rd century.[ten]

The value at its introduction was 10 asses, giving the denarius its proper name, which translates equally "containing 10". In almost 141 BC, it was re-tariffed at 16 asses, to reflect the decrease in weight of the as. The denarius continued to be the master coin of the Roman Empire until information technology was replaced past the so-chosen antoninianus in the early 3rd century Advertising. The coin was terminal issued, in bronze, nether Aurelian between AD 270 and 275, and in the offset years of the reign of Diocletian. ('Denarius', in A Dictionary of Ancient Roman Coins, past John R. Melville-Jones (1990)).[11] [12]

Debasement and evolution [edit]

| Yr | Consequence | Weight | Purity | Note[thirteen] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 267 BC | Predecessor | six.81 g | ? | 1⁄48 pound. Equals 10 asses, giving the denarius its name, which translates every bit "containing ten". The original copper coinage was weight-based, and was related to the Roman pound, the libra, which was about 325 g. The basic copper coin, the as, was to weigh 1 Roman pound. This was a large cast coin, and subdivisions of the as were used. The "pound" (libra, etc.) connected to exist used every bit a currency unit of measurement, and survives e.g. in the British monetary system, which all the same uses the pound, abbreviated as £. |

| 211 BC | Introduction | 4.55 thousand | 95–98% | 1⁄72 pound. Denarius commencement struck. According to Pliny, it was established that the denarius should be given in substitution for x pounds of bronze, the quinarius for v pounds, and the sestertius for two-and-a-half. Simply when the equally was reduced in weight to one ounce, the denarius became equivalent to 16 asses, the quinarius to 8, and the sestertius to four; although they retained their original names. Information technology as well appears, from Pliny and other writers, that the ancient libra was equivalent to 84 denarii. |

| 200 BC | Debasement | 3.9 g | 95–98% | 1⁄84 pound. |

| 141 BC | Debasement | 3.nine g | 95–98% | ane⁄84 pound. Retariffed to equal 16 asses due to the decrease in weight of the equally. |

| 44 BC | Debasement | 3.ix g | 95–98% | Death of Julius Caesar, who set the denarius at 3.nine g. Legionary (professional soldier) pay was doubled to 225 denarii per year. |

| Advertizement 14–37 | three.ix k | 97.5–98% | Tiberius slightly improved the fineness as he gathered his infamous hoard of 675 one thousand thousand denarii. | |

| 64–68 | Debasement | 3.41 chiliad | 93.5% | 1⁄96 pound. This more closely matched the Greek drachma. In AD 64, Nero reduced the standard of the aureus to 45 to the Roman pound (7.2 g) and of the denarius to 96 to the Roman pound (3.30 g). He as well lowered the denarius to 94.5% fine. Successive emperors lowered the fineness of the denarius; in 180 Commodus reduced its weight past one-eighth to 108 to the pound. |

| 85–107 | Debasement | 3.41 g | 93.five% | Reduction in silver content under Domitian |

| 148–161 | Debasement | 3.41 g | 83.5% | |

| 193–235 | Debasement | three.41 yard | 83.five% | Several emperors (193–235) steadily debased the denarius from a standard of 78.5% to 50% fine. In 212 Caracalla reduced the weight of the aureus from 45 to l to the Roman pound. They also coined the aes from a bronze alloy with a heavy lead admixture, and discontinued fractional denominations below the as. In 215 Caracalla introduced the antoninianus (five.1 g; 52% fine), a double denarius, containing 80% of the silver of two denarii. The coin invariably carried the radiate imperial portrait. Elagabalus demonetized the coin in 219, but the senatorial emperors Pupienus and Balbinus in 238 revived the antoninianus as the principal argent denomination which successive emperors reduced to a less intrinsically valuable billon coin (2.60 g; 2% fine). |

| 241 | Debasement | iii.41 g | 48% | |

| 274 | Double Denarius | 3.41 g | v% | In 274, the emperor Aurelian reformed the currency and his denominations remained in use until the great recoinage of Diocletian in 293. Aurelian struck a radiate aurelianianus of increased weight (84 to the Roman pound) and fineness (5% fine) that was tariffed at five notational[ clarification needed ] denarii (sometimes called "common denarii" or "denarii communes" by modern writers, although this phrase does not announced in any ancient text). The coin carried on the reverse the numerals XXI, or in Greek κα (both meaning 21 or 20:one). Some scholars believe that this shows that the coin was equal to xx sestertii [ description needed ] (or 5 denarii), but it is more likely that it was intended to guarantee that it contained 1⁄xx or 5% of silverish, and was thus slightly better than many of the coins in apportionment. The aureus (minted at l or 60 to the Roman pound) was exchanged at rates of 600 to 1,000 denarii, equivalent to 120 to 200 aurelianiani. Rare fractions of billion[ clarification needed ] denarii, and of statuary sestertii and asses, were also coined. At the same fourth dimension, Aurelian reorganized the provincial mint at Alexandria, and he minted an improved Alexandrine tetradrachmon that might[ clarification needed ] have been tariffed at par with the aurelianianus. The emperor Tacitus in 276 briefly doubled the silver content of the aurelianianus and halved its tariffing[ clarification needed ] to 2.five d.c. (hence[ description needed ] coins of Antioch and Tripolis (in Phoenicia) carry the value marks X.I), but Probus (276–282) immediately returned the aurelianianus to the standard and tariffing[ clarification needed ] of Aurelian, and was the official tariffing until the reform of Diocletian in 293. |

| 735 | Novus denarius (new penny) | Pepin the Short ( r. 751–768–), the outset king of the Carolingian dynasty and begetter of Charlemagne, minted the novus denarius ("new penny"): 240 pennies minted from 1 Carolingian pound. So a single money independent 21 grains of silver. Effectually 755, Pepin'southward Carolingian Reform established the European monetary system, which can be expressed every bit: one pound = 20 shillings = 240 pennies. Originally the pound was a weight of silverish rather than a coin, and from a pound of pure silver 240 pennies were struck. The Carolingian Reform restored the silverish content of the penny that was already in circulation and was the straight descendant of the Roman denarius. The shilling was equivalent to the solidus, the money of account that prevailed in Europe before the Carolingian Reform; information technology originated from the Byzantine gold coin that was the foundation of the international monetary organization for more than than 500 years. Debts contracted before the Carolingian Reform were defined in solidi. For 3 centuries following the Carolingian Reform, the but coin minted in Europe was the silver penny. Shillings and pounds were units of account used for convenience to express large numbers of pence, not actual coins. The Carolingian Reform also reduced the number of mints, strengthened royal authority over the mints, and provided for uniform design of coins. All coins bore the ruler'southward name, initial, or title, signifying purple sanction of the quality of the coins. Charlemagne spread the Carolingian system throughout Western Europe. The Italian lira and the French livre were derived from the Latin discussion for pound. Until the French Revolution, the unit of account in French republic was the livre, which equalled 20 sols or sous, each of which in turn equalled 12 deniers. During the Revolution the franc replaced the livre, and Napoleon's conquest spread the franc to Switzerland and Belgium. The Italian unit of business relationship remained the lira, and in Britain the pound-shilling-penny relationship survived until 1971. Even in England the pennies were eventually debased, leaving 240 pennies representing essentially less than a pound of silver, and the pound as a monetary unit became divorced from a pound weight of silver. Afterwards the breakup of the Carolingian Empire pennies debased much faster, particularly in Mediterranean Europe, and in 1172 Genoa began minting a silver money equal to four pennies. Rome, Florence, and Venice followed with coins of denominations greater than a penny, and tardily in the twelfth century Venice minted a silvery coin equal to 24 pennies. By the mid-13th century Florence and Genoa were minting gold coins, effectively ending the reign of the silver penny (denier, denarius) as the only circulating money in Europe. | ||

| 757–796 | Penny | Offa, king of Mercia, minted and introduced to England a penny of 22.v grains of silver. The coin'southward designated value, however, was that of 24 troy grains of argent (ane pennyweight, or 1⁄240 of a troy pound, or about 1.56 grams), with the difference being a premium attached by virtue of the minting into coins (seigniorage). The penny led to the term "penny weight". 240 actual pennies (22.five grains; minus the 1.5 grain for the seigniorage) weighed merely 5,400 troy grains, known equally a Saxon pound and later known as the tower pound, a unit used only by mints. The tower pound was abolished in the 16th century. Even so, 240 pennyweights (24 grains) made one troy pound of silver in weight, and the monetary value of 240 pennies also became known as a "pound". The silvery penny remained the primary unit of coinage for about 500 years. | ||

| 790 | Penny | one.76g | 95–96% | Charlemagne new penny with smaller diameter only greater weight. Boilerplate weight of 1.7 g, just ideal theoretical[ clarification needed ] mass of ane.76 g. Purity is from 95% to 96%. |

| c. 1527 | Penny | i.58g | 99% | Belfry pound of 5400 grains abolished and replaced by the Troy pound of 5760 grains. |

| 1158 | Penny | 92.five% | The purity of 92.5% silvery (i.due east. sterling silver) was instituted by Henry Ii in 1158 with the "Tealby Penny" — a hammered coin. | |

| 1500s | Penny | By the 16th century information technology contained well-nigh a third the silverish content of a Troy pennyweight of 24 grains. | ||

| 1915 | Penny | The penny, now struck in bronze, was worth around one-6th of its value during the Center Ages. British government sources suggest that there has been a 6100% price aggrandizement since 1914. |

Value, comparisons and silver content [edit]

| Marco Sergio Silo: 116–115 BC | |

|---|---|

| |

| Helmeted caput of Rome | Galloping Knight belongings the sword and a barbarian'southward caput |

| Denarius: Sergio one | |

one gold aureus = 2 golden quinarii = 25 silver denarii = 50 silver quinarii = 100 bronze sestertii = 200 bronze dupondii = 400 copper asses = 800 copper semisses = 1,600 copper quadrantes[ when? ]

It is hard to give even rough comparative values for money from before the 20th century, as the range of products and services available for purchase was so different. During the republic (509 BC–27 BC), a legionary earned 112.five denarii per year (0.3 denarii per day). Under Julius Caesar, this was doubled to 225 denarii/yr, with soldiers having to pay for their own nutrient and arms,[14] while in the reign of Augustus a Centurion received at least 3,750 denarii per year, and for the highest rank, 15,000 denarii.[15]

By the tardily Roman Republic and early Roman Empire (c. 27 BC), a mutual soldier or unskilled laborer would exist paid 1 denarius/solar day (with no taxation deductions), effectually 300% inflation compared to the early on period. Using the cost of bread as a baseline, this pay equates to around US$xx in 2013 terms.[16] Expressed in terms of the price of silver, and bold 0.999 purity, a one⁄x troy ounce denarius had a precious metal value of around Us$2.60 in 2021.[17]

At the height of the Roman Empire a sextarius (546ml or about 2 1/4 cups) of ordinary wine cost roughly one Dupondius (⅛ of a Denarius), after Diocletian's Edict on Maximum Prices were issued in Advertizement 301, the same detail cost eight debased common denarii – 6,400% inflation.

Silver content plummeted across the lifespan of the denarius. Under the Roman Empire (later on Nero) the denarius contained approximately 50 grains, 3.24 grams, or 1⁄10 (0.105ozt) troy ounce. The fineness of the silver content varied with political and economic circumstances. From a purity of greater than ninety% silver in the 1st century AD, the denarius fell to under 60% purity past AD 200, and plummeted to 5% purity past AD 300.[eighteen] By the reign of Gallienus, the antoninianus was a copper coin with a sparse silver launder.[xix]

Influence [edit]

In the final years of the 1st century BC Tincomarus, a local ruler in southern Great britain, started issuing coins that appear to take been made from melted down denarii.[twenty] The coins of Eppillus, issued around Calleva Atrebatum around the aforementioned time, announced to accept derived design elements from various denarii such as those of Augustus and M. Volteius.[21] [20]

Even after the denarius was no longer regularly issued, it continued to exist used equally a unit of measurement of account, and the proper noun was applied to afterwards Roman coins in a way that is not understood. The Arabs who conquered large parts of the country that once belonged to the Eastern Roman Empire issued their own gilded dinar. The lasting legacy of the denarius can be seen in the use of "d" equally the abbreviation for the British penny until 1971.[22] It besides survived in French republic as the name of a coin, the denier. The denarius besides survives in the common Standard arabic proper noun for a currency unit, the dinar used from pre-Islamic times, and still used in several modernistic Arab nations. The major currency unit of measurement in quondam Principality of Serbia, Kingdom of Serbia and erstwhile Yugoslavia was dinar, and it is notwithstanding used in present-day Serbia. The Macedonian currency denar is too derived from the Roman denarius. The Italian word denaro, the Spanish word dinero, the Portuguese word dinheiro, and the Slovene word denar , all significant money, are also derived from Latin denarius. The pre-decimal currency of the Great britain until 1970 of pounds, shillings and pence was abbreviated every bit lsd, with "d" referring to denarius and standing for penny.

Apply in the Bible [edit]

In the New Testament, the gospels refer to the denarius as a day'due south wage for a common laborer (Matthew 20:2,[23] John 12:five).[24] In the Book of Revelation, during the Third Seal: Black Horse, a choinix ("quart") of wheat and iii quarts of barley were each valued at one denarius.[25] Bible scholar Robert H. Mounce says the price of the wheat and barley equally described in the vision appears to exist ten to twelve times their normal toll in ancient times.[26] Revelation thus describes a condition where basic goods are sold at profoundly inflated prices. Thus, the black horse rider depicts times of deep scarcity or famine, but non of starvation. Manifestly, a choinix of wheat was the daily ration of one adult. Thus, in the atmospheric condition pictured past Revelation 6, the normal income for a working-class family unit would buy enough food for only one person. The less costly barley would feed three people for i twenty-four hour period's wages.

The denarius is also mentioned in the Parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37). The Render unto Caesar passage in Matthew 22:15–22 and Mark 12:13–17 uses the word (δηνάριον) to describe the money held upward by Jesus, translated in the King James Bible as "tribute penny". It is unremarkably thought to be a denarius with the head of Tiberius.

Encounter also [edit]

- Denarius of L. Censorinus, for the detailed description of a specific Roman denarius

- Dupondius

- French denier

- Gilded Dinar

- Ides of March Coin

- Macedonian denar

- Sestertius

- Solidus (money)

- Tribute penny

Notes [edit]

- ^ Its value was increased to 16 assēs in the center of the 2nd century BC.

References [edit]

- ^ Crawford, Michael H. (1974). Roman Republican Coinage, Cambridge University Press, 2 Volumes. ISBN 0-521-07492-4

- ^ David. L. Vagi. Coinage and History of the Roman Empire, c. 82 BC–Ad 480. Vol. Two. Sydney, Ohio: Money World.

- ^ A Lexicon of Greek and Roman Antiquities, William Smith, D.C.l., LL, D., John Murray, London 1875 Pg 393, 394

- ^ Metcalf, William E. (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage. New York: Oxford University Printing. p. 300. ISBN978-0-19-937218-8.

- ^ The Numismatic Round, Volume 8–9, Spink & Son, 1899–1900 Piccadilly Westward, London

- ^ Handbook to Life in Aboriginal Rome, Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins. Oxford University Press, New York 1994.

- ^ As the Romans Did, Jo-Ann Shelton. Oxford University Press, New York 1998

- ^ Plutarch's Lives, Vol two, John Langhorne, DD, William Langhorne, AM, London 1813

- ^ The New Bargain in Old Rome, HJ Haskell, Alfred K Knoff New York 1939

- ^ Ancient coin collection 3Wayne G Sayles Pg 21–22

- ^ "Aurelian, Roman Majestic Coinage reference, Thumbnail Index". Wildwinds.com. Retrieved 24 August 2006.

- ^ "Aurelian Æ Denarius. Rome mint. IMP AVRELIANVS AVG, laureate, draped & cuirassed bust right". Wildwinds.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2006. Retrieved 24 August 2006.

- ^ Kenneth West. Harl (12 July 1996). Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. to A.D. 700. JHU Press. pp. 94–5. ISBN978-0-8018-5291-half-dozen. .

- ^ Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy A.; Adkins, Both Professional Archaeologists Roy A. (2014-05-14). Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome. Infobase Publishing. ISBN978-0-8160-7482-two.

- ^ Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy A.; Adkins, Both Professional Archaeologists Roy A. (2014-05-xiv). Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome. Infobase Publishing. p. 79. ISBN978-0-8160-7482-2.

- ^ "Ownership Power of Ancient Coins". Archived from the original on x February 2013.

- ^ "XE: Convert XAG/USD. Silverish to United States Dollar". world wide web.xe.com . Retrieved 2021-01-28 .

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-xi-28. Retrieved 2015-12-01 .

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create as title (link) - ^ Katsari, Constantina (2002). "The Concept of Inflation in the Roman Empire". Economic History . Retrieved 2006-12-06 .

- ^ a b De Jersey, Philip (1996). Celtic Coinage in Britain. Shire Publications. pp. 29–30. ISBN0-7478-0325-0.

- ^ Bean, Simon C (1994). "The coinage of Eppilus" (PDF). The coinage of Atrebates and Regni (Ph.D.). University of Nottingham. pp. 341–347. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ English Coinage 600–1900 by C.H.V. Sutherland 1973 ISBN 0-7134-0731-Ten p.10

- ^ "Matthew 20:ii NIV – He agreed to pay them a denarius". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2013-ten-02 .

- ^ "Jn 12:5; NIV – "Why wasn't this perfume sold ..." Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2013-10-02 .

- ^ Revelation 6:half dozen

- ^ The New International Commentary on the New Testament, "The Book of Revelation," p. 155)

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Denarius. |

- Denarius

- From Octavian to Augustus: Images Illustrating His Rise to Ability

- Denarius – A Roman soldier's daily pay

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denarius#:~:text=Expressed%20in%20terms%20of%20the,around%20US%242.60%20in%202021.

Posted by: kennedyenone1944.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Much Is A Denarius In Today's Money"

Post a Comment